THE BAD

With continuing research into mast cells, new insights are being developed and the list of conditions, disorders and diseases that include mast cell involvement is growing. Below are just a few of the disorder categories where mast cells are involved.

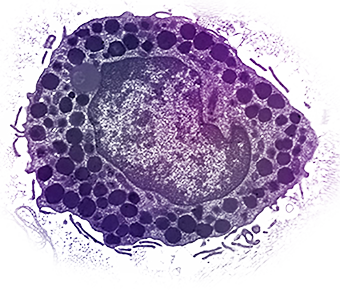

Mast Cell Disorders

As described by The Mastocytosis Society, there are two main forms of mast cell disorders: Mastocytosis, where the body produces too many mast cells, and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome (MCAS), where even the normal number of mast cells are too easily activated by a trigger to release their contents, called mediators. These mediators can cause a variety of unpredictable symptoms in both children and adults, including skin rashes, flushing, abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, vomiting, headache, bone pain and skeletal lesions, and anaphylaxis. Triggers can be heat, cold, stress (physical or emotional), perfumes or odors, medications, insect stings, and foods. These symptoms are treated with medications including antihistamines, mast cell stabilizers, and leukotriene inhibitors, while anaphylaxis is a medical emergency requiring epinephrine.

Mastocytosis can affect skin and internal organs such as the bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, liver, and spleen. Most patients with mastocytosis have cutaneous (skin) or indolent (benign) systemic forms, but aggressive disease can occur, which may require chemotherapy.

Allergic Disease

Many forms of cutaneous and mucosal allergy are mediated for a large part by mast cells; they play a central role in asthma, eczema, itch (from various causes) and allergic rhinitis and allergic conjunctivitis. Antihistamine drugs act by blocking the action of histamine on nerve endings. Cromoglicate-based drugs (sodium cromoglicate, nedocromil) block a calcium channel essential for mast cell degranulation, stabilizing the cell and preventing release of histamine and related mediators. Leukotriene antagonists (such as montelukast and zafirlukast) block the action of leukotriene mediators, and are being used increasingly in allergic diseases.

Anaphylaxis

In anaphylaxis (a severe systemic reaction to allergens, such as nuts, bee stings or drugs), body-wide degranulation of mast cells leads to vasodilation and, if severe, symptoms of life-threatening shock.

Autoimmunity

Mast cells are implicated in the pathology associated with the autoimmune disorders rheumatoid arthritis, bullous pemphigoid, and multiple sclerosis. They have been shown to be involved in the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the joints (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis) and skin (e.g. bullous pemphigoid) and this activity is dependent on antibodies and complement components.

Reproductive Disorders

Mast cells are present within the endometrium, with increased activation and release of mediators in endometriosis. In males, mast cells are present in the testes and are increased in oligo- and azoospermia, with mast cell mediators directly suppressing sperm motility in a potentially reversible manner.